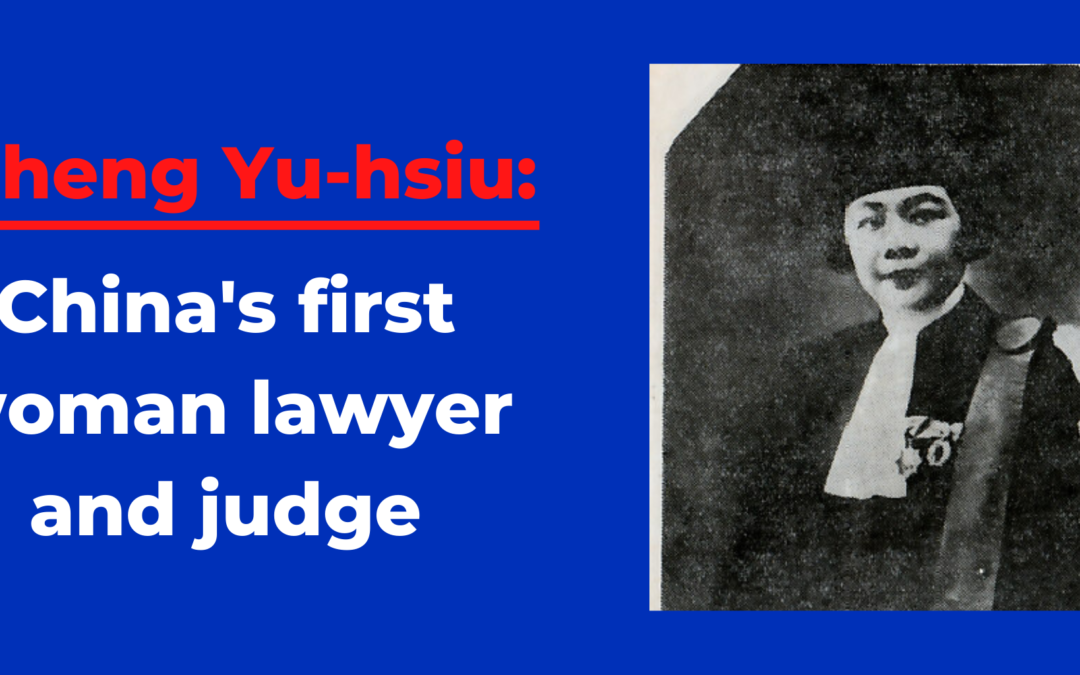

Tcheng Yu-hsiu was by turns a diplomat, a lawyer, a judge, a legislator, an author – but at all times she was a rebel.

The story of China’s first woman lawyer and judge is as colourful as the period of Chinese history through which she lived and practised. Her rebellious streak and string of unique accomplishments characterise a remarkable career.

Born in Shenzhen in 1891, Yu-hsiu was a rule breaker from the very beginning. She refused to comply with several traditions which typically applied to young Chinese girls at the time, including refusing to bind her feet at age 6. When her parents arranged her marriage to the son of an official at age 13, she personally wrote to her fiancé to dissolve the engagement.

After running away from home and spending time studying in Japan, Yu-hsieu found herself compelled by the cause of a revolutionary group called the Tongmenghui, whose goals included overthrowing the Qing dynasty in favour of establishing a Chinese Republic. After playing a part in an attempted assassination, her revolutionary thinking led her to the study of law with the hopes of creating change.

It was during her time in France that she played an important role in international politics.

Yu-hsiu moved to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne, where she gained a masters and a doctorate in law. It was during her time in France that she played an important role in international politics. In 1919, the Paris Peace Conference was underway and the Chinese delegation was on the verge of agreeing to concede formerly German territory in China to the Japanese. This was fiercely opposed by Chinese expats in France who were aware of the discussions and Yu-hsiu was tasked with stopping the agreement going through.

She allegedly did so in a most unusual way. When the head of the Chinese delegation was taking a walk in the garden of his residence, Yu-hsiu appeared with what looked like a gun in her sleeve and threatened to shoot him if he signed the agreement. The Chinese delegation never ended up signing the agreement and Yu-hsiu would take the rosebush branch she feigned as a gun back to her home in China, displaying it in her living room.

Her legal renown, including acting in a prominent divorce between two famous Opera stars, sooned earned her the post of a judge in a court in Shanghai’s French Concession

It was in France that she met her husband, the distinguished lawyer Wei Tao-ming. Together, the two returned to Shanghai where they established a legal practice together, making Yu-hsiu the first woman to practise as a lawyer in the country. Her legal renown, including acting in a prominent divorce between two famous Opera stars, soon earned her the post of a judge in a court in Shanghai’s French Concession – thereby making her the first woman judge in China.

Yu-hsiu used her increasingly prominent voice to advocate for women’s empowerment in China and channeled this into her work when she was appointed as a legislator for the Kuomintang Party. On top of this, she eventually became the President of the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law.

In 1944, Yu-hsiu published her autobiography ‘My Revolutionary Years’ under her married name Madame Wei Tao-ming. At the end of her career, she retired with her husband in the United States, where she spent the last of her years.

Sources & further reading: