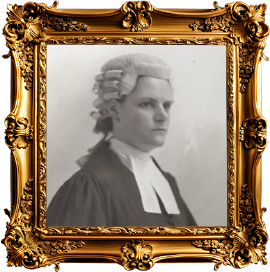

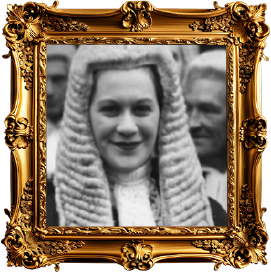

Her Honour Judge Joanna Korner CMG QC is a Crown Court judge, former prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the UK candidate for this year’s judicial elections to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. She was also a speaker at our 2017 Spark21 Conference.

Just before the election process begins, we talk to Judge Korner about her fascinating career, female representation in international law and the advice she would give to aspiring international lawyers.

Q: Judge Korner, what first drew you to a career in law?

A: My father suggested that law was a suitable career for someone who was naturally so argumentative!

The international law career came after 25 years as a criminal barrister. One day in 1998 at an International Bar Association conference in Vienna, I found myself listening to Louise Arbour, Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), in a debate with Steven Kay QC about the Tadić case. Louise was one of the most impressive speakers I’d ever heard. I approached her afterwards to tell her this and how inspiring I thought her work was, which is something I’d never done before to someone I didn’t know.

A short time later, I was contacted by Geoffrey Nice, (who later prosecuted Milošević at ICTY), to organise advocacy training for the prosecutors there. During the course, I met the Deputy Prosecutor, Graham Blewitt and then Louise and they asked if I would be prepared to come and prosecute a case at the Tribunal – of course, I agreed. The following year, Louise contacted me to say that Radoslav Brđanin and Momir Talić had been arrested, and that was my first international case.

“With every case, we were genuinely developing international criminal law”

Q: How did your experience at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) shape your career?

A: Having spent a number of years at the Bar prosecuting and defending in all manner of criminal cases, I accepted a job in the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICTY. I knew it would be a challenge and I wasn’t disappointed: my years at the ICTY were the defining experience of my career. I was dealing with historical events, and I knew that the investigations and trials at ICTY was the only opportunity for any kind of justice to be offered to the victims of these egregious crimes. With every case, we were genuinely developing international criminal law: there was little jurisprudence to guide us, save for the relatively small amount established by the Nuremberg/Tokyo Tribunals. We had to find new methods of investigation, of obtaining evidence and doing trials. It also gave me the opportunity to work with all manner of people – not just lawyers – from different backgrounds and appear before judges from diverse legal traditions. The experience made domestic practice less satisfying and accordingly I took an appointment as a Crown Court judge.

“Training lawyers and judges, particularly from the next generation, is a great passion of mine”

Q: What have been the other high points of your legal career thus far?

A: On a domestic level, my first high point was obtaining a tenancy at 6 Kings Bench Walk, then the Chambers of John Leonard QC. Two other highlights were first in 1993 when I took Silk, and second in 2004 when I was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) for services to international law.

Working as a Senior Prosecutor at ICTY from 1999 – 2004 and then again from 2008 – 2012 started an affinity with Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). In 2005, I worked as the Chief Legal Advisor to the Prosecutor of BiH (2004 – 2005) to assist in the establishment of the War Crimes Department, and later wrote two OSCE reports (2016 and 2020) on improving war crimes processing in the country.

Finally, training lawyers and judges, particularly from the next generation, is a great passion of mine. As the Head of International Training for the Advocacy Training Council (now the ICCA) and then as International Course Director of the Judicial College, I conducted courses both in the UK and internationally on advocacy, substantive international criminal law and aspects of trial procedure.

Q: What drives you to seek election as a judge of the International Criminal Court?

A: The ICC offers the only hope of justice for many victims of the most egregious crimes and I wish to see such victims receive the justice they deserve. I believe my experience can be of assistance in the achievement of that goal.

In a lengthy legal career, I have built up extensive expertise in domestic and international criminal law with 8 years at the ICTY and 27 years as a part- and then full-time judge presiding over more than 500 complex trials, such as large-scale fraud, serious sexual offences, gang violence and murder. I also have proven experience working alongside colleagues from diverse legal traditions and managing multinational teams. As an expert in handling vulnerable witnesses and conducting long and complex trials, I have trained judges and lawyers from more than 25 countries around the world, and have also delivered advocacy training for UN agencies, Special Tribunal for the Lebanon, ICTY, ICTR and the ICC

Finally, during my years at ICTY I took part in the early years of the development of ICL and would wish to continue to play a part in its development and consolidation.

Q: Currently, one third of the International Criminal Court’s judges are women, compared to one sixth of the UK Supreme Court’s and roughly one fifth of the Court of Appeal’s. The ICC’s current Prosecutor is female and, a few years ago, it had a female President, First Vice-President and Second Vice-President, all at the same time.

Why is this gender parity at the top important and is there anything that national legal systems, including the UK’s, can learn from the ICC’s relative success in this area?

A: Gender parity is obviously important for a number of reasons, including, but not limited to:

- The judiciary is not trusted if entirely male;

- The composition of the judiciary should be transparent, inclusive and representative;

- Diversity enhances the legitimacy of the court and;

- It enlarges the scope of discussion as women bring their lived experience to judicial actions.

However, it is equally important that those selected for the Bench should have the qualities that make them good judges – regardless of gender.

The common-law system differs from that of the civil law system in that in the former judges are selected from those who have had considerable experience as lawyers or academics, whilst in the latter becoming a judge is selected at a young age as a career path. Both systems have advantages and drawbacks. In the context of gender parity in the UK, women did not join the legal profession in large numbers until the early 1980s. Many abandoned practice after a few years for family or economic reasons. Accordingly, it is only in recent years that appointments to the Bench have reflected the numbers of women with the required experience and qualities who have applied for such appointment.

The ICC has a unique system of judge selection in that it has a List A and List B. Criteria for the latter does not include a requirement of practice before a court. Nominations are made by the State Parties to the Statute who also vote for the candidates. Whilst the Rome Stature says that the State Parties shall “take into account a fair representation of male and female judges” it must also take into account the legal systems and geographical representation. Accordingly, it would be difficult and in my view undesirable to marry such a system to that operated in the UK.

Q: There are quite a few women prosecutors in highly visible positions at the moment, from the new EU Prosecutor appointment in Laura Codruta Kövesi to Kamala Harris, Democratic running mate in the US presidential election. What are the qualities that make prosecutors strong public office holders?

A: Prosecutors represent the state; it is sometimes said they should act as “ministers of state” or, as was once famously said by Sir John Nutting QC, “the prosecution win no victories and suffer no defeats”. A good prosecutor will therefore be one who acts with fundamental fairness and honesty, has credibility and is trusted by judges and his/her opponents. As the tortuous process for the election of a new ICC prosecutor has shown, it has become important that a prosecutor possesses personal moral, as well as professional integrity. The ability to master a brief at speed and good judgement should not be overlooked and an ability to work with a diverse group of people, is a key quality of most successful prosecutors.

All these qualities are equally applicable to public office holders. However, it is interesting to note that Kamala Harris gave as her reason for becoming a prosecutor: “I ran for elected office so I could be in charge and use the law as a force for change. When you are in charge you don’t have to ask permission to do the right thing.” It is, to say the least, debatable that the job of a prosecutor is to use the law for this purpose rather than applying the law with integrity and independence.

“you stood out amongst a sea of male faces“

Q: How have you found being a woman in law? Do you think it affected your career and experience of the legal profession? If so, how?

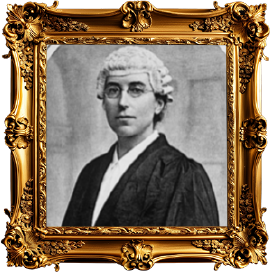

A: When I started practice there were relatively few women practising at the Criminal Bar. I was extremely fortunate in that my pupil supervisor, Ann Curnow QC, was one of the outstanding advocates, male or female, practising in crime. She demonstrated that it was possible for a woman to reach the top and acted as a mentor throughout my career. Whilst there were certain judges who were condescending and clients who objected to being represented by a woman, these were rare occurrences. In one sense, being a woman at that time was a positive advantage, in that you stood out amongst a sea of male faces. This aspect was, I believe, one of the reasons why I was given Silk somewhat earlier in my career than my male contemporaries.

I should add that I loved my time at the Bar. Each case was different and stimulating and properly remunerated. Chambers were smaller and its members went there most days after court, which assisted with the establishment of good relationships and the ability to develop a Chambers “ethos”.

The Criminal Bar, whilst competitive, was a friendly social milieu without many of the pressures which are now all too common. It is a matter of much regret that the publicly-funded part of the profession which I joined – and which is vital to maintain a strong and once-admired part of the criminal justice system – has changed so dramatically for the worse. It has become one which is undervalued by successive governments, is expected to do more work for less money and consequently provides little job satisfaction.

Q: What advice do you have for people, particularly women, who are embarking on a career in international law?

A: First, get a mentor: as already stated my career was advanced tremendously with the help of my mentor, who happened to be my supervisor during pupillage. As my mentor, she was an inspiration not only to me, but to many other women embarking on their legal careers.

Second, recognise that it is now a difficult field to break into ; there are so few tribunals left. Accept jobs which are stepping- stones – an internship with an NGO, for example, might not be your ultimate goal, but it brings you contacts. Networking is half the battle. And do not turn down an offer because you feel that you do not have sufficient experience: accept the challenge.